|

A novice fisherman should therefore be

prepared to invest a certain amount of time - in reconnaisance

and study - before he starts catching fish!

- It all starts in freshwater

where spawning takes place.

- © photo Steen Ulnits

Several external factors rule the life

of a seatrout. Knowledge of these factors will highly increase

the catches of any fisherman, be he a spinning addict or a flyfishing

fanatic. Two of the most important factors are food and the physical

condition of the water. Where food can be found, seatrout will

be present too! After all, food is the primary reason for the

trout migrating into the sea.

For that reason it is very important that

visiting fishermen keep an eye open for food items present in

the piece of water that he has chosen to fish. If he sees fleeing

baitfish, hiding crustaceans or wiggling worms, he is on the

right track. Then sooner or later seatrout will be there too.

But if he sees nothing, chances are that there will be no seatrout

either.

If you want to catch seatrout on a regular

basis, you have to know about their annual migrations and changing

habitats. Seatrout migrate a lot - most along open shorelines,

least in secluded bays. They are either following bait or migrating

back and forth between their spawning and their feeding grounds.

Thus we are dealing with two seemingly

different kinds of seatrout - one that wants to feed and one

that wants to spawn.

Spring

In early spring the spring migration begins

- from freshwater or brackish water into the open sea. The exact

time for this migration depends on both the time of year, the

location and the prevailing water temperature.

- In early spring sea

trout stay in brackish bays like this.

- © photo Steen Ulnits

If the winter is mild or the water brackish,

the migration from the rivers and secluded bays may begin early

in the year. But after a cold winter or in places with a high

salinity, migration will begin later - typically in March-April.

And if spring sets in suddenly, migrations may start - and end

- very quickly. Following a mild winter, migrations will start

more slowly and will last longer.

If the winter has been long and cold -

with ice covering the water - you may experience fantastic fishing

just after iceout. A large number of fish will have congregated

in the brackish bays, where they are very hungry. And since food

is still scarce, the fish are easy to catch. Conversely, after

a mild winter fish will be spread over a larger area - many in

the open sea at an early time. Here they are more difficult to

locate - and catch.

After spawning seatrout quickly regain

the weight they lost in freshwater. Often the spawned-out "kelts"

are followed by a different kind of seatrout - the small but

fat and silvery "grønlændere" who are

immature seatrout that have not spawned yet. Unfortunately, they

are often just under the legal size limit of 40 cm's and thus

have to be returned unharmed.

"Grønlændere" may

never have entered freshwater during the winter months. They

may have stayed in brackish water all winter where they have

been feeding actively. Come spring they follow the bigger seatrout

out into the open sea where they feed voraciously on baitfish,

crustaceans and worms.

Summer

When the water temperature rises, so does

the seatrout's tolerance towards the salinity of the water. During

the warm summer months the seatrout has no problems whatsoever

with true oceanic water - with a salt content as high as 35 o/oo.

- Come summer, sea trout

will be in salty ocean water like here on Djursland.

- © photo Steen Ulnits

But water temperature can get too high

for seatrout. When it approaches 20 degrees Celsius, seatrout

escape the heat by migrating out towards deeper and colder water.

This typically happens in July which marks the coming of true

summer. May and June still offer excellent seatrout fishing for

those willing to fish through the night - during the "light

nights" as we call them in Denmark.

But the warm coastal waters of summer still

hold an abundance of food. Seatrout know that and seek the shallows

at night time when the water is at its coldest and prey most

active. Come sunrise, seatrout again abandon the shallows and

seek the cold of deeper water.

If you want to catch seatrout during the

heat of summer, it has to take place during the darkest hours

of the night. If you have access to a boat, you can seek the

fish in deeper water during the day. Unfortunately, seatrout

out here are often digesting the food they ate during the night.

Thus they are not very interested in eating any more - until

after the next sunset.

Daytime fishing can still be productive

though - at places where strong currents and deep water meet

within reach close to shore.

Autumn

Spring and summer have been used to grow

fat and ready for the spawning migration of autumn. This migration

is often triggered by the first storms and rainfalls of August-September.

Immediately the fish sense that autumn is around the corner -

spawning season too.

Most of the larger fish have already left

the sea and entered the rivers in May-June. The majority of smaller

fish stay in the salt for an additional few months and do not

start the spawning migration until now.

Often they congregate in smaller schools

of similar sized fish. Some males and females may already have

teamed up in pairs. If you meet groups of mature seatrout like

these, you may be in for the best and most exciting fishing of

the year!

Don't be afraid of inclement weather when

it comes to fishing for these lightly coloured fish. In fact

the fishing typically improves as the weather gets worse. Calm

and sunny weather usually makes these fish almost impossible

to catch. But inclement weather really turns them on!

Often these mature fish of autumn can be

caught in exactly the same spots where the spawned-out kelts

of spring were encountered. And often it pays to fish during

night time where migrations mostly take place.

Points projecting from the coastline are

always the best bet. Here the fish often stop for a break during

their migration.

Winter

Come winter, all mature seatrout have left

the salt and entered the rivers. Still you may encounter small

immature "grønlændere" or large "overspringere"

- fish that for some reason have chosen not to spawn that particular

year - in the ocean. The latter form sort of a reserve if some

diasaster should wipe out all fish in the river.

These silvery and immature fish continue

their nonstop feeding in the salt as long as the water is warm

enough and the food plenty enough. As the water temperature drops,

the fish seek from the salty open sea into secluded bays where

freshwater outlets have made the water more brackish. Here they

will spend the winter. They are still feeding but their appetite

drops with the dropping water temperature. Thus they become more

difficult to catch.

It is very difficult to generalize about

the effects of water temperature on fish behaviour. This is especially

so when the salinity of the water has to be taken into account

too. But if we are to do it anyway, then always and if possible

avoid temperatures below 5 degrees. If the water temperature

is somewhere in between 5 and 15 degrees Celsius, seatrout thrive

- no matter how high the salinity.

In the wintertime, open and salty waters

are usually devoid of seatrout. They have either left to spawn

in the rivers, or they have sought more brackish water in the

bottom of secluded bays. This is where we find them when winter

is giving way to spring - after iceout. From then on their appetite

just grows and grows, often resulting in pure feeding frenzies

on warm sunny days.

Not surprisingly the best early spring

fishing is usually to be had on sunny days where the water really

has picked up some warming rays from the sun. Shallow water normally

produces most fish as it warms faster than deeper water.

When the upcoming spring migration has

spread the seatrout over a larger area, they have again become

more difficult to find - and catch. But they still hunt aggressively

- if you encounter them. And come the heat of summer, the places

used for overwintering have often become muddy and depleted of

oxygen - now totally unattractive to the fish.

The year of the seatrout has come to an

end - and a new has begun!

"Bay trout"

and "herring feeders"

In larger bay areas you may come across

a type of seatrout that does not follow the Year of the Seatrout.

It is the so-called "fjordørred" - "bay

trout" - which resides permanently in the bay all year round.

Quite often it never turns silvery like most seatrout. Instead

it retains a golden hue with lots of black spots all year round.

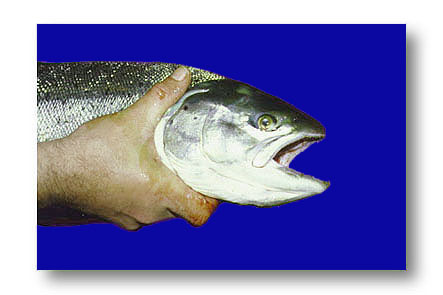

- Big sea trout like this

4 kg specimen become exclusive herring feeders.

- © photo Steen Ulnits

Occasionally you may even encounter a bay

trout with remaining red spots - a leftover from its time in

freshwater. A good example of the fact that seatrout and brown

trout are in fact one and the same species - they just happen

to live in different environments. Bay trout feed mostly on smaller

baitfish and crustaceans - only rarely do they attack larger

fish.

The exact opposite goes for the so-called

"sildeædere" - "herring feeders" -

who do just that: Feed exclusively on large herring and sprat.

They may have the same parents as the bay trout but at some time

in life they decided for a different way of living.

When reaching a size of maybe 3-4 pounds,

small food items don't really fill up the stomachs of seatrout

any longer. Therefore they turn their interest towards larger

food items.

They migrate out into deeper water where

they lock on to schools of sprat, herring and sand eels. On this

new diet the seatrout start to grow very rapidly. They have also

become fish that shoreline fishermen seldom encounter any more.

They live way out and deep down where only boat fishermen stand

a chance of catching them.

But they grow rapidly and reach sizes comparable

to salmon. Seatrout weighing 10-20 pounds are not unusual among

the schools of sprat, herring and sand eels!

© 2006 Steen Ulnits

|